2025 MICHIGAN RECAP: Gaps

Nebraska tests itself vs. a playoff-caliber team and finds some holes — especially on the lines

This week’s sections are:

Stunts Are Getting The Defense Obliterated — And It May Have To Keep Doing Them

Offensive Outliers And What They Tell Us About The Gameplan

The Tackling Seems Bad

Wide Zone Is Also An Issue

One Thing The Offense Probably Should Have Done More Of

Some Reasons For Hope On Defense

Turnover Margin Tracker

Stunts Are Getting The Defense Obliterated — And It May Have To Keep Doing Them

“Stunting” or “twisting” — a rush tactic where front-seven defenders exchange their gaps or paths after the snap in an effort to cause blocking confusion, generate angles, and create penetration and chaos — is something Nebraska’s relied on since switching to the 3-3-5 defense before the 2023 season. For “light-box” defenses — like the 3-3-5 — with the run fit frequently playing at a disadvantage to the offense, stunts and twists are often a good answer, as a sort of way to counteract the offense’s superior blocking numbers with unpredictability and surprise that can cause negative plays or make an OC think twice about running it right at you. And they’re useful in pass-rush situations for generating missed assignments in pass protection rules that can spring rushers free to pressure the quarterback. Stunts and twists are often a tool defensive coaches turn to when they feel like their rushers are struggling to win one-on-one and could use a schematic advantage, though they are often deployed with good rush groups, too, to make them even more effective.

Tony White used stunts and twists heavily in his time as Nebraska’s defensive coordinator; his rate of true “loop” stunts was around 18% of plays in each of the last two years. The strategy isn’t new to Nebraska’s defensive scheme.

What is new, under first-year coordinator John Butler, is that Nebraska is now stunting on nearly half of its plays. Entering the Michigan game, Nebraska was at a 38.3% stunt rate, then vs. the Wolverines was at 53.7%.

And the stunts have been effective: Nebraska’s plays with a stunt entering the Michigan game had a 72.7% success rate — 10 percentage points higher than NU’s overall defensive success rate — and their snaps vs. UM with a stunt had a 72.4% success rate, compared to a 48.0% success rate on plays without a stunt. This isn’t a post to say the stunts aren’t working or haven’t been more effective than base calls. They are working and have been more effective than base calls.

But what is happening is that Nebraska’s failed stunts — where the defenders are not correctly executing the movement or reaching their assigned gap as they switch spots — are getting the defense killed.

All three long Michigan runs — which I think more-or-less decided a close game in UM’s favor — came off a botched stunt movement, at least initially.

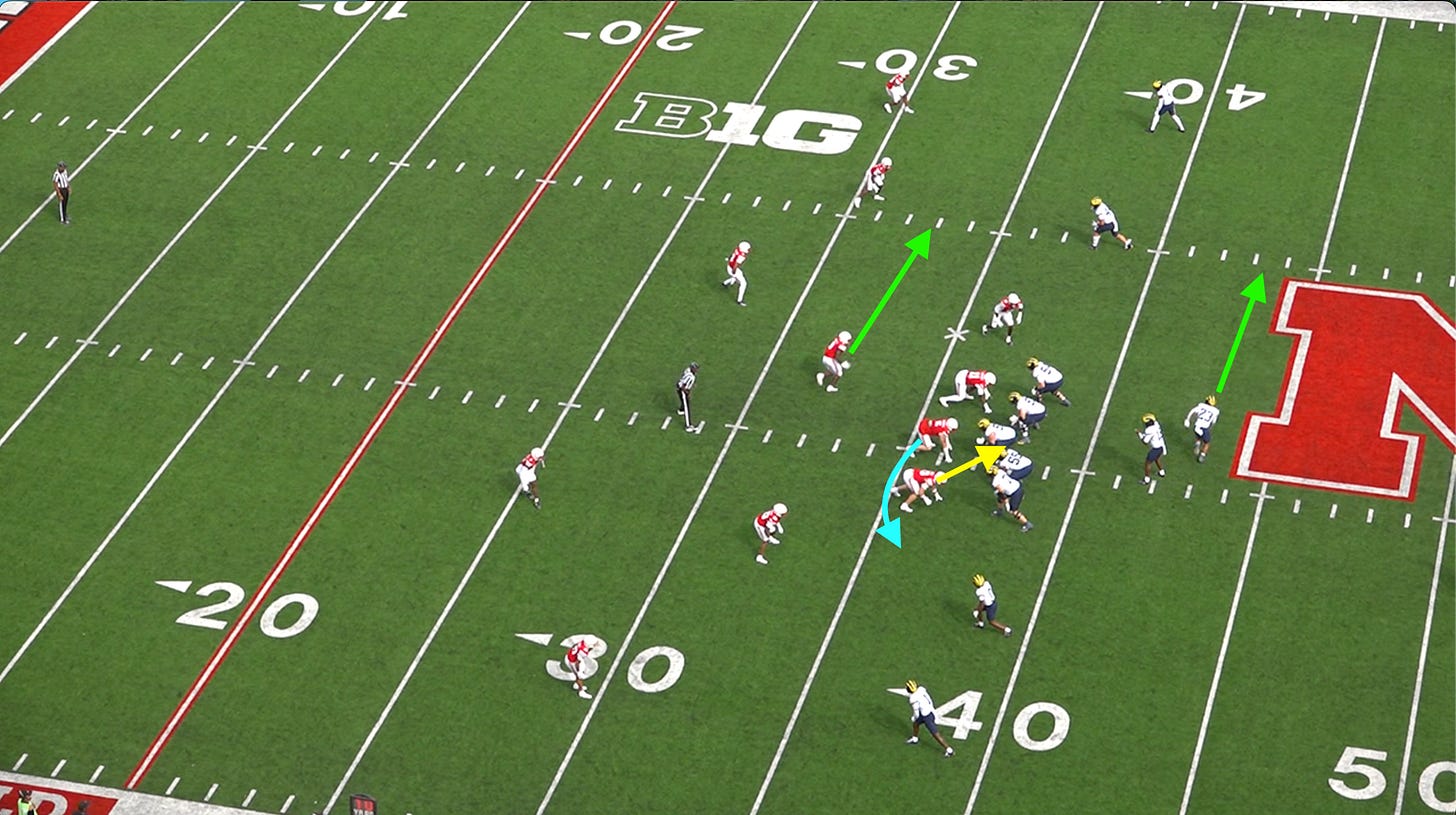

The first long run was quarterback Bryce Underwood’s carry off an empty quarterback draw. Michigan starts the play in a spread 2x2 look, with Nebraska in a 4-1 shell and two deep safeties. Michigan then further de-loads the box by running the back out of the backfield on a motion, sucking the linebacker with him (green arrows below), even though Nebraska is in Cover 4 and it’s not his assignment to travel with motion (the color guy on the TV broadcast said this play was man coverage but was incorrect.) A 4-0 box vs. empty is already a tough situation for the defensive line —with only the four NU defensive linemen in the box and five Michigan lineman to block them. That’s already putting Nebraska at a disadvantage.

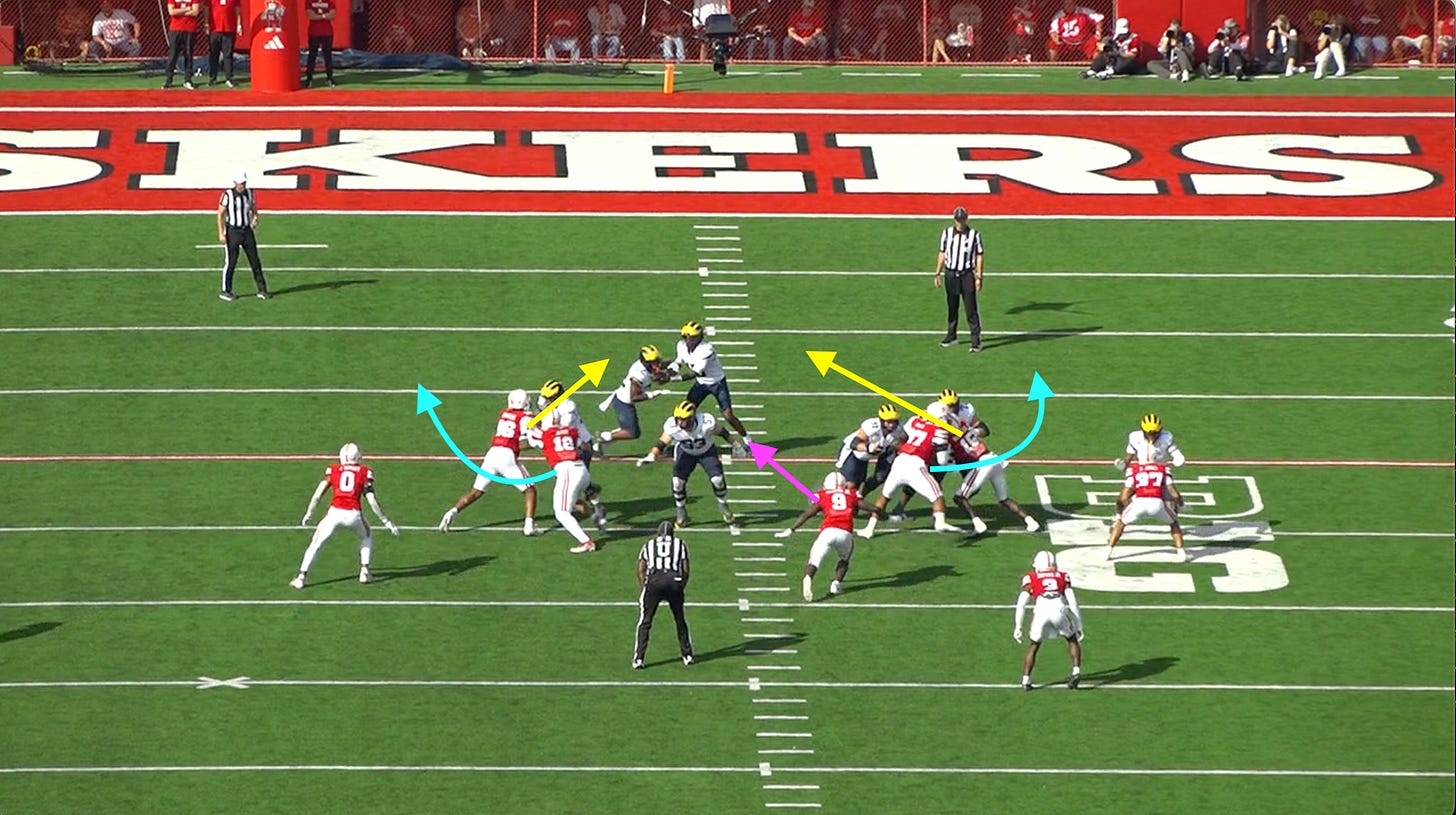

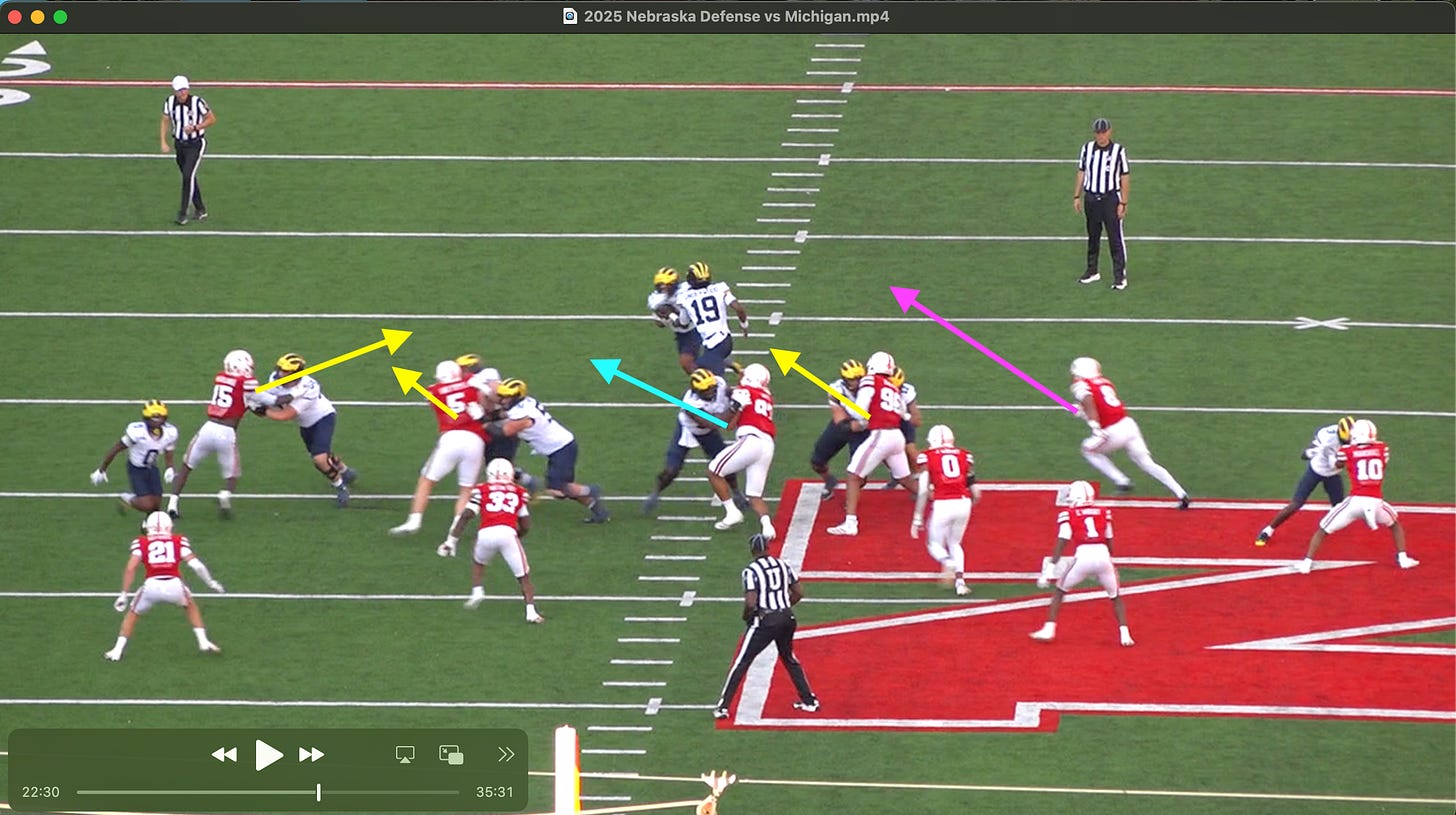

Making this more challenging is that NU has an “ET” stunt on, meaning the defensive end/edge defender and defensive tackle are switching gaps. Stunt verbiage lists the player crashing down first and the looper second, so an “ET” means the edge (yellow arrow) is the crasher and the tackle (blue arrow) is the looper:

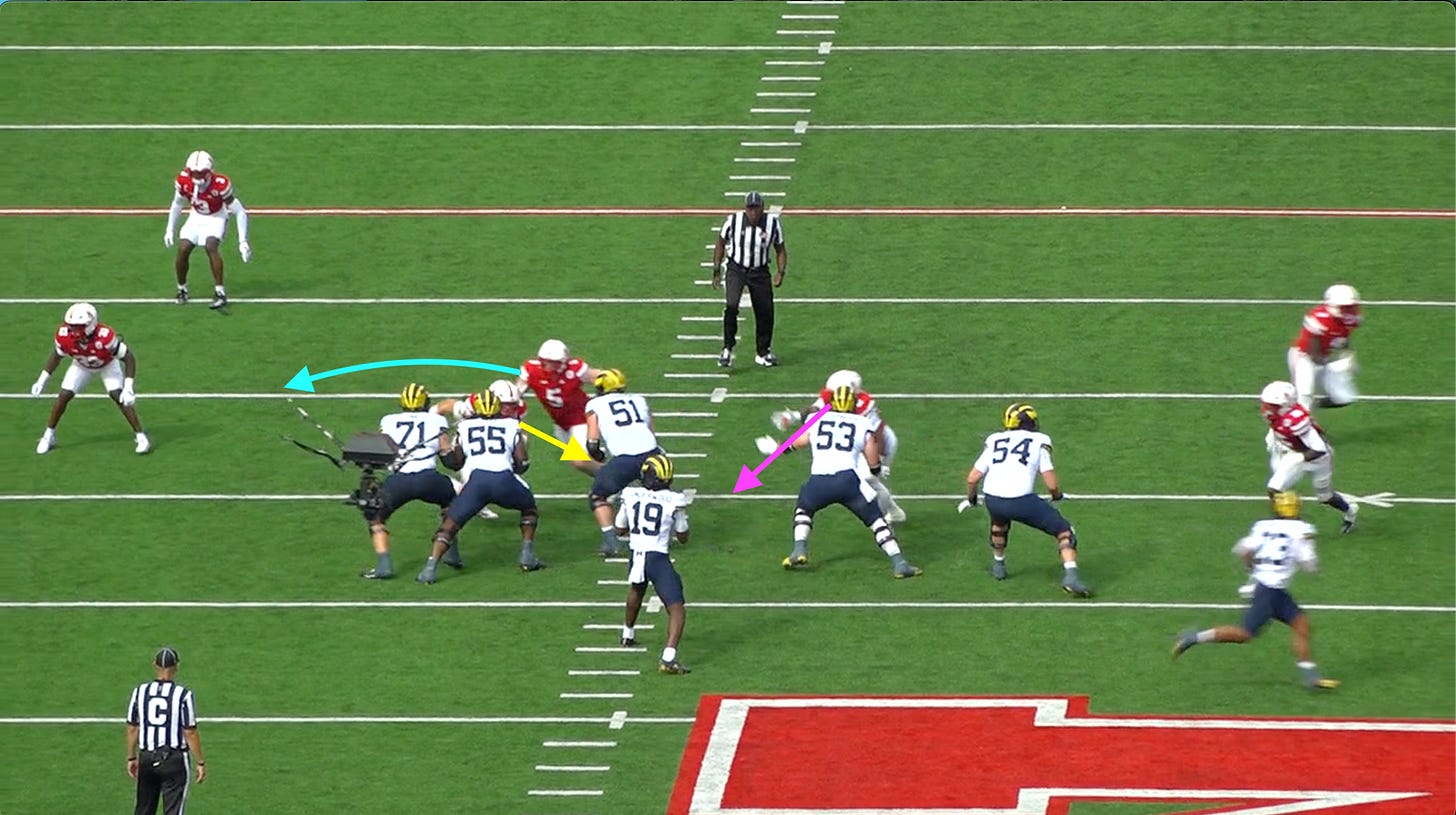

At the snap, the edge fills down and the tackle loops, but the tackle doesn’t generate enough push to get back to interior player’s A gap, and the backside end in the Odd front (purple arrow below) crashes inside, too, either as part of the stunt or as a mistake/error:

The result is the looper still going to the edge, the crasher stuck on an offensive linemen, and the other end also pushed down to join them: three Nebraska defenders bunched all walled off to the boundary, with just the backside edge rushing upfield, creating a huge hole:

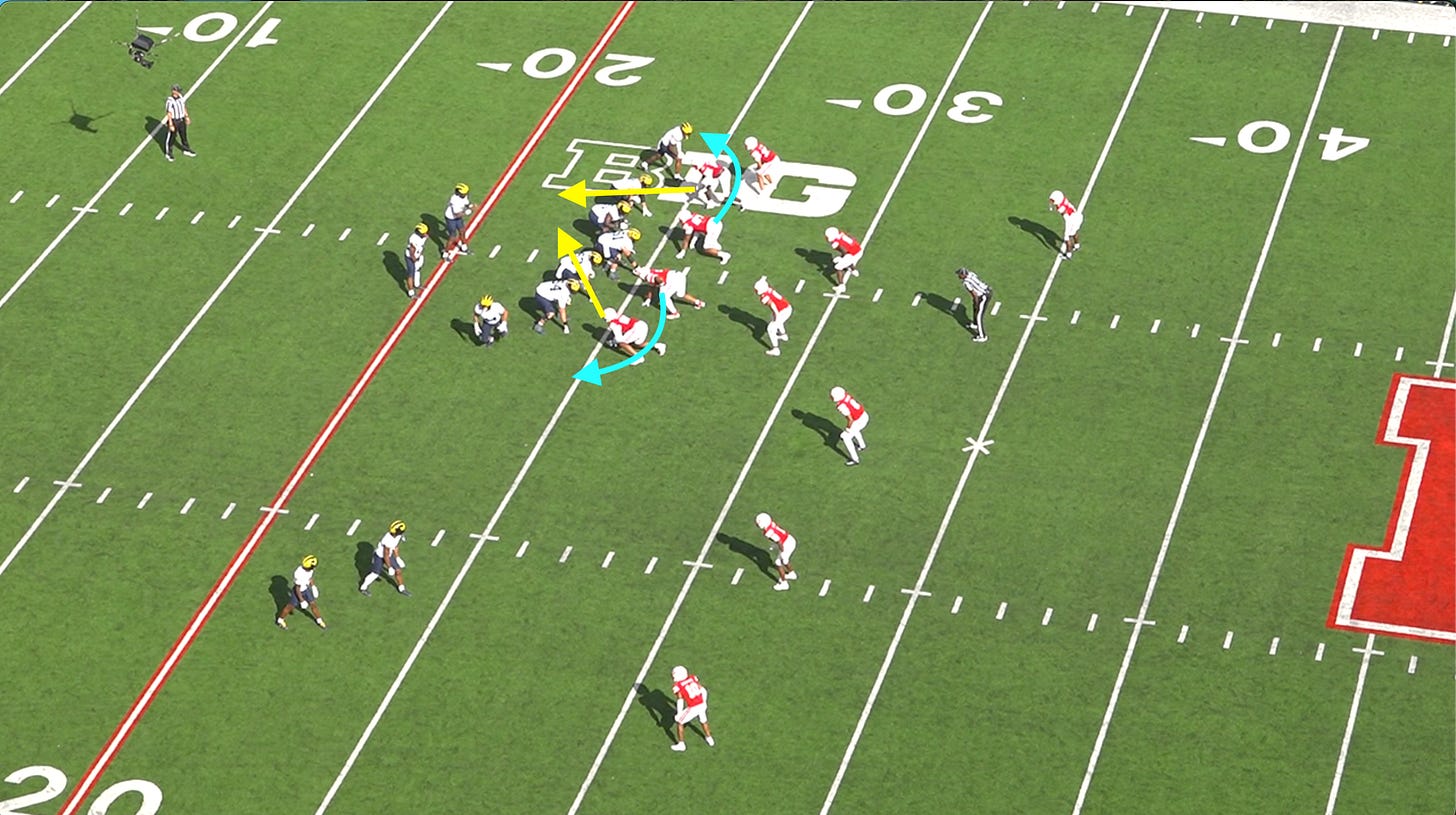

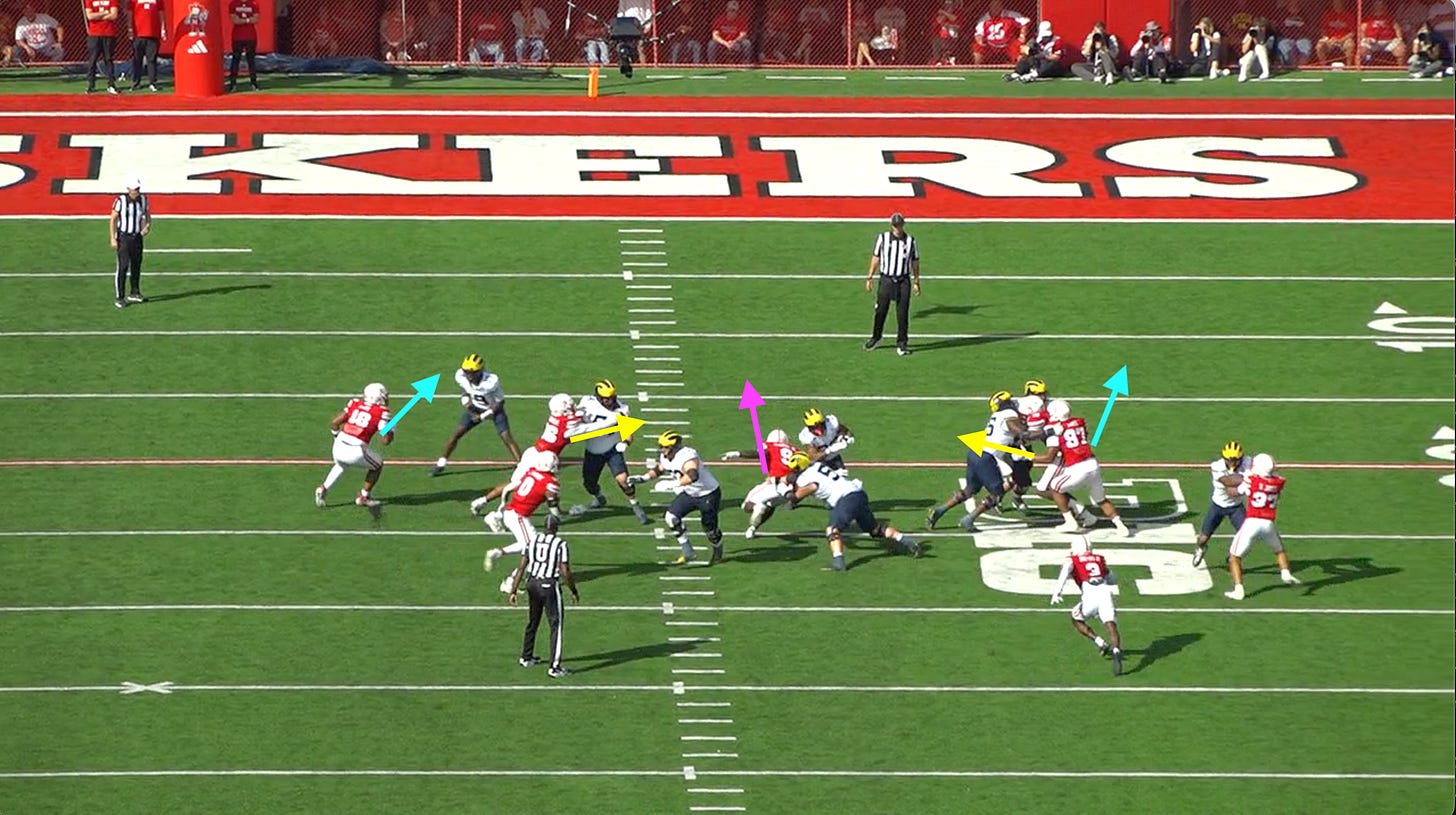

On the second long run — a 75-yarder by Justice Haynes — Nebraska had a Double ET stunt on, meaning the same action as the last play but to both sides of the line, with both edges crashing and both tackles looping:

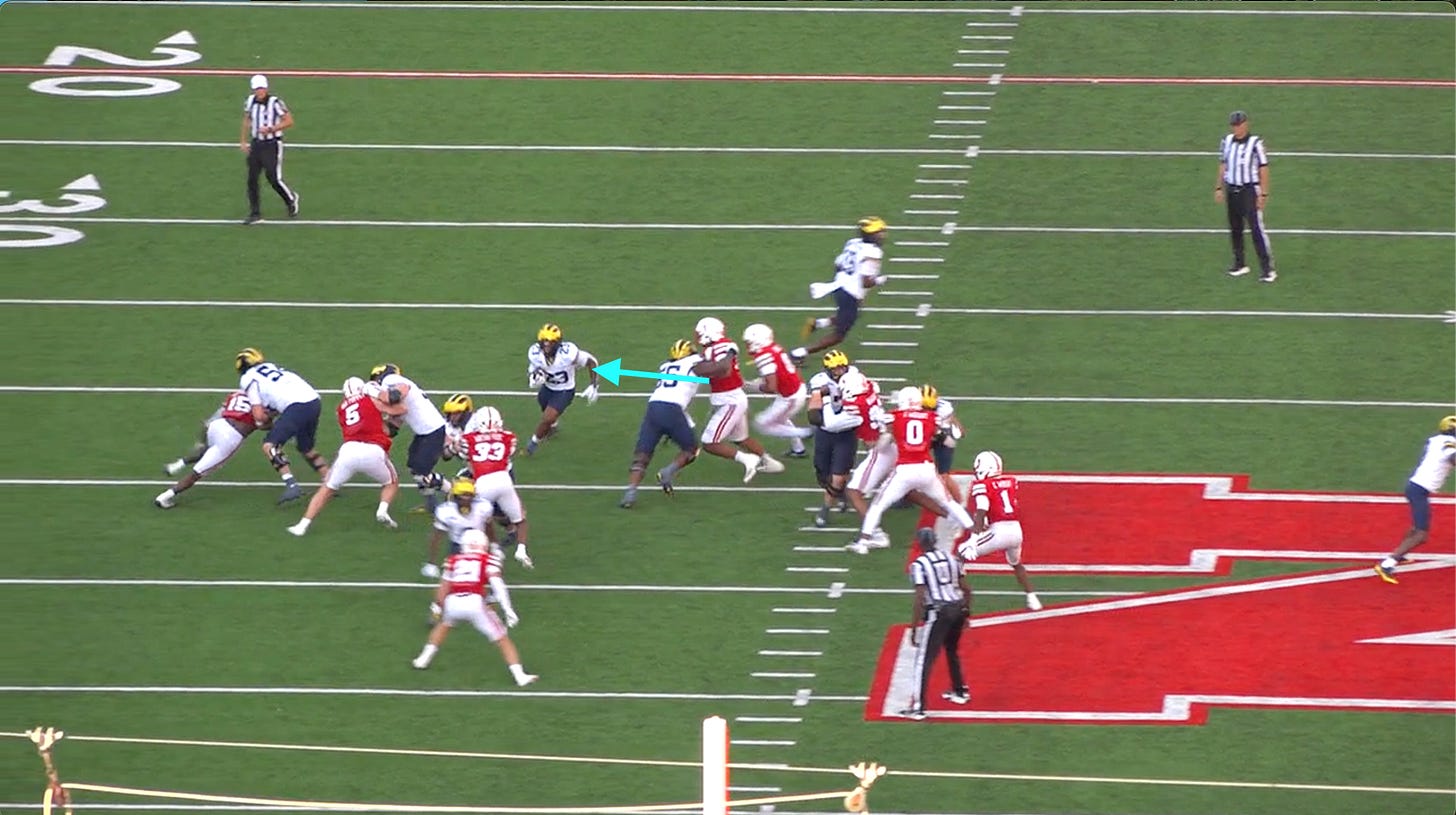

Michigan has a Wide Zone play on — more on that in a later section. Both tackles loop out of the A gaps on the stunt at the snap, but neither crasher is able to get back to the tackles’ original gaps, leaving a huge hole up the middle in the A gaps, with just inside linebacker Vincent Shavers (purple arrow) there to fill the two gaps:

With the ball now in the back’s hands, the crashers still are walled off from the A gaps, the tackles have now looped themselves to the outside of the line, and Shavers fills one of the A gaps …

… and the back takes the ball into the other, and we’re off to the races after deep safety Marques Buford misses a tackle.

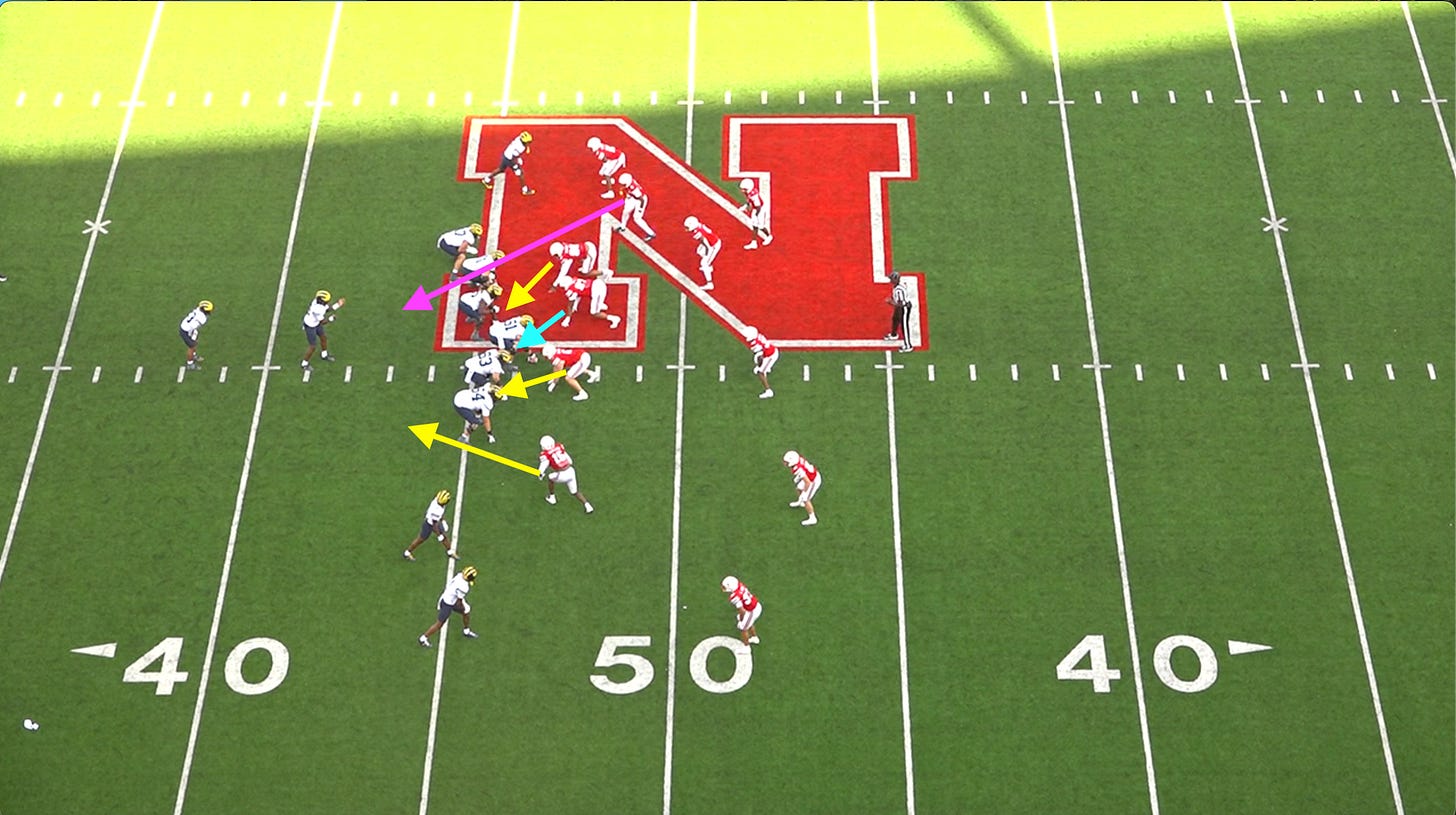

The third long run — from 54-yards out by Jordan Marshall — also came off a stunt, but wasn’t a twist with a looper and is instead a “shift” stunt.

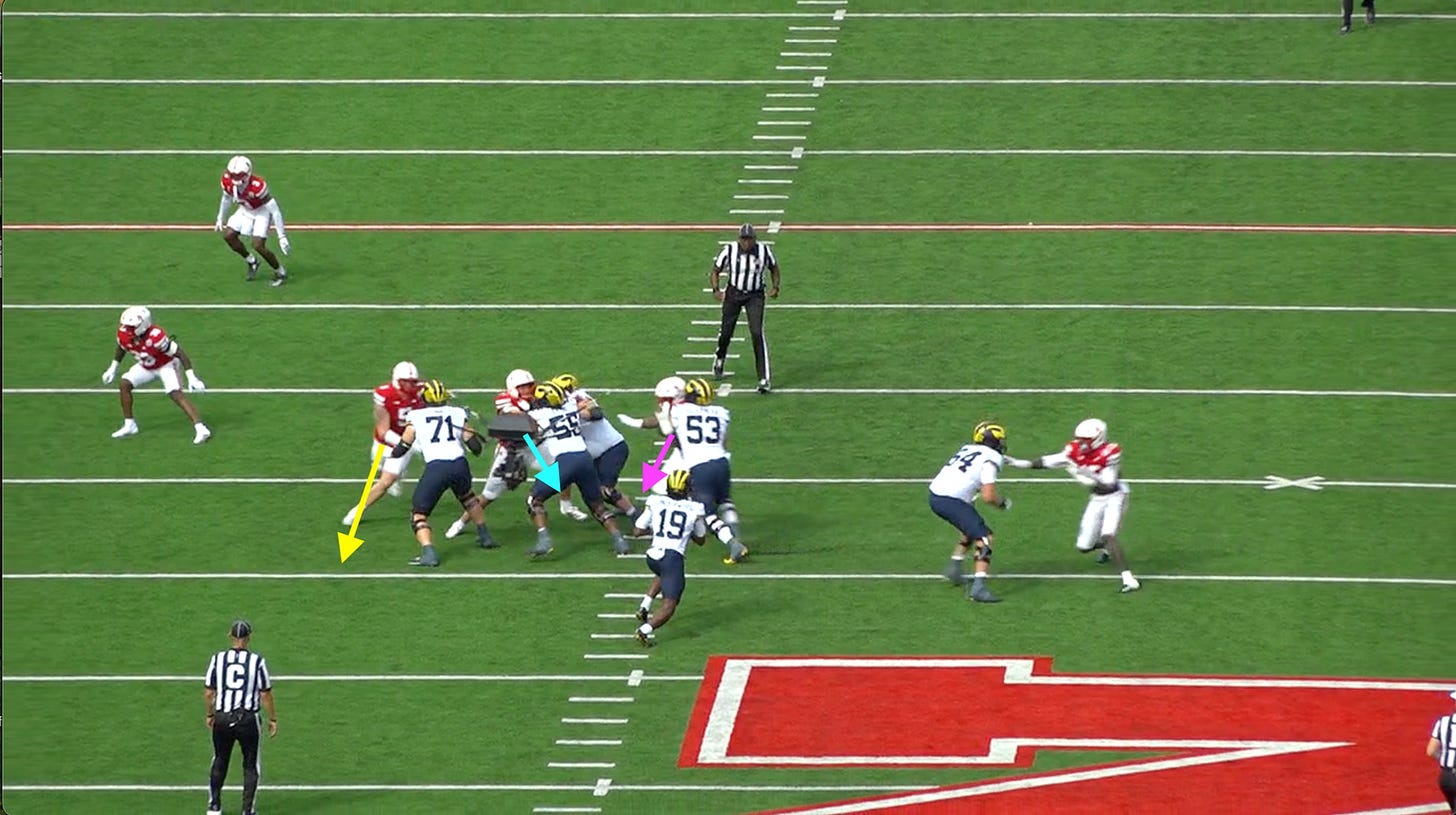

On the third play, Nebraska is bringing an edge blitz to the strength of the formation (purple arrow), and has three of its defensive line stunt one gap over to the weakside to clear space for the blitzer. So, Nebraska’s defensive end now fills the A gap, it’s 3-tech now fills the opposite A gap, and the nose tackle shifts to the B gap — everyone moving over one gap:

This stunt gets blown when the 3-tech (the blue arrow above) isn’t able to cross the center’s face and gets walled off, leaving no one in the opposite A gap, with the nose vacating it to shift over for his responsibility on the stunt:

The 3-tech on this play was Gabe Moore, a transfer who hadn’t really played in the previous games but was subbing in throughout Saturday. Moore aligns wide here considering that he’s supposed to be in the opposite-side A gap after the snap, to the point I think he’s misaligned:

At the snap, Michigan has Wide Zone on again, to the weak side of the formation. The blitz comes off the edge to the strong side, and the other two stunting defensive linemen fight over one gap to close their gaps. But Moore gets walled off and can’t cross the center’s face:

Resulting in another mammoth hole and touchdown:

Any of those three stunts being properly executed, and Nebraska might be 4-0.

It is tough to blame the player execution totally, though, when stunts are being called on half the defense’s plays. If you run something enough, inevitably someone will make a mistake. And mistakes on stunts lead to the busts we saw. By calling stunts and twists so much, NU’s staff is opening the defense up to surrendering moonshots like these.

Long-term, this puts Nebraska’s defensive staff in a bit of a pickle.

On one hand, you can’t stop calling the stunts. They’ve been undeniably effective so far (remember, 10 percentage points higher by success rate than non-stunt plays) and are delivering some of the defense’s best reps. Stunts are the most effective (and seemingly only) tool the defensive staff has to generate havoc right now; it can’t just stop calling them.

But calling them this often is leading to reps of missed execution, and that missed execution is leading to the 500-foot homers we’re seeing the defense give up against the Power 5 teams it’s faced.

So, what do you do? Limit how much you’re calling your best defensive strategy to stop giving up the big plays? Or keep doing it at a high rate because it’s so effective and live with the huge gashes?

I don’t know the answer, but I’m also not a defensive coordinator making a million dollars. They’ve got a bye week to figure out the right balance.

Offensive Outliers And What They Tell Us About The Gameplan

Nebraska used pre-snap motion against Michigan on Saturday more often than it has in any game I’ve charted in my four previous years of doing this blog. NU used pre-snap motion on 51 plays (or 70.8% of the time), plus had two more pre-snap shifts (with multiple players moving), bringing the total usage of pre-snap movement to 73.6% of plays. The season average entering had been about 50%, and the highest previous game I had charted had been a 60% against Ohio State last season, and the highest seasonlong rate NU has used motion was 53.0% for Scott Frost’s 2021 offense. NU was way above any of those Saturday.

It was also nearly the highest usage I’ve charted of condensed looks — alignments where the receivers are in tight to the body of the formation and not split out as wide — in the last two years since I started tracking that element. Saturday’s condensed rate was 48.6% of plays, trailing only last year’s Colorado game, when 56.1% of snaps came out of condensed looks.

It was also a high mark for “empty” alignments, where the QB is aligned in the backfield without anyone next to them. Nebraska was in empty for 11 plays Saturday, or 15.3% of snaps. NU had used empty just 10 times in the season entering the Michigan game and had only been above a 10% empty usage in a handful of games over the past four years, the highest being a 13.0% usage against Northwestern in 2023. On Saturday, seven of those empty alignments occurred in the first half, so it was not a halftime adjustment to the pressure the offensive line was giving up, but rather a determined element in the initial script.

Nebraska also had a very elevated usage rate of “Slide” and “Arrow” run-pass options Saturday. Slide RPOs feature a flat route — often looking like a blocker on the Split Zone run concept — coming across the formation, and Arrow RPOs feature a quick flat route to the outside for the quarterback to take. The QB is reading an edge defender on both RPOs — if the edge stays wide, hand the ball off to the back; if the edge crashes, pitch it out to the flat into the open space.

All of those elements being that high gives us some insight into how Nebraska’s staff best thought they could attack Michigan’s defense:

One, the staff thought they needed misdirection, late changes to the picture, and playing off expectations to move the ball. The use of pre-snap motion was often to disguise an alignment and less to “learn information,” which tells me NU’s staff thought it was important to disguise their looks or change them just before the snap to catch Michigan off guard. They heavily utilized a package with running back Isaiah Mozee aligned as a bunch receiver where Mozee went in motion (Mozee went in motion nine times Saturday; he had been the motion player just twice total with the starters entering this game), where it ran him in Orbit and looping manners to serve as eye candy for the Michigan defense. The heavy Split Zone/Slide usage also tells me they wanted to present one thing to the Michigan defense and then do another — those Split Zone and Slide plays look identical right until the split-flow blocker leaks out into the flat for a pass route.

Two, Nebraska thought its best way to win was going to be through spread-out decision making. The high empty rate would be a huge indicator of this: Against heavy-pressure and disguise-based teams, like Nebraska faced in the Wolverines, one common answer is to get into empty alignments. With all five eligibles spread out, it forces defenses to widen or spread to cover the receivers, which can undo some of the disguise and better declare for the offense which defenders are blitzing and which are in coverage.

For example, a defense might have a mugger-heavy pressure package on with muggers arrayed in the center of the formation, but if the offense checks to an empty alignment that spreads the formation, those muggers that are in coverage may have to detach from the spine of the formation and go out wide to be in position to cover their responsibilities. The muggers who remain are your blitz threats. And now you have a better picture of who’s blitzing and who’s in coverage.

We saw this a lot vs. Michigan: Raiola motioned the back out of the backfield and set them as a receiver and then reevaluated the defensive picture on nine plays Saturday.

The downside comes in that lining up in empty can also be a liability in protection against a pressure team, as you open yourself up to the defense bringing more rushers than you have blockers and not having any secondary pass-protection help, like a back, if someone loses. Which requires the quarterback diagnosing the rush and getting the ball out of their hands quickly to the open space. Nebraska put that trust on Raiola to diagnose and get the ball out in empty a lot Saturday. The results were mixed: NU had five plays out of empty that gained 11, 12, 10, 9 and 6 yards. But a lot of the havoc plays by UM’s defense were also coming with no back in to protect: two of the sacks came out of empty, as did Raiola’s interception.

The heavy use of those Slide/Arrow RPOs also indicates a reliance on putting the ball in Raiola’s hands to make a decision in space. These plays essentially turn into triple option looks, with the ability to give the ball to the back up the middle, pitch it out to the Arrow/Slide player heading to the edge, or for the quarterback to keep it if the defense overplays the Arrow/Slide, with the quarterback often rolling out of the pocket to evaluate the defense and make the decision. That NU ran so many of these Saturday says the staff felt there was an increased need for this optionality and “making the defense wrong post-snap” against Michigan.

Three, NU wanted to attack the flats and the sidelines in the passing game and create situations where middle-of-the-field defenders were running through traffic.

Nebraska’s offensive staff rarely challenged middle-of-the-field defenders with true dropback concepts. Condensed formations are often used as ways to pull defenders into the spine of the defense and then run out-breaking routes and concepts, like Sail or Flood, etc., with the extra space created to the outside of the formation by aligning the receivers to the outside of the formation. Those Arrow/Slide RPOs also attack the outside portion of the field in the passing game. In the opposite, running inside-breaking routes out of condensed splits — like deep crossers or Dagger — are excellent ways to put many defenders in the middle of the field and create situations where they are having to cross each other to the outside, especially against man coverage.

All of this sort of adds up to a gameplan, to me, that says Nebraska’s offensive staff knew it was physically overmatched by the Michigan defense. Turning to setting new records for motion and shifting, option-based RPOs, and varying spread and tight looks to get the defense to declare is not the gameplan of a team that thinks it can line up and take somebody on straight up. That’s not to say that many of those ideas aren’t sound practices or effective decisions when facing any very good/elite defense — which I believe Michigan has — but it’s just to say that the staff prepped for the game to be at a talent disadvantage. I’m sure they didn’t expect the tackles to get abused to the degree they did at times, but it’s worth noting that NU knew it was going to have to do some small-ball things to move down the field.

The Tackling Seems Bad

The other obvious issue the defense seemed to encounter was tackling. Missed tackles were less of a factor on the big runs than the stunts, but there were several other key plays where NU had the chance to get Michigan ball-carriers on the ground to end a drive and didn’t, including a couple times on that late drive where Michigan ate up most of the fourth quarter.

One of the new elements I’ve been tracking this year is missed tackles on Nebraska’s defense and where they’re coming from. I previously relied on Pro Football Focus for that but found myself questioning/unsure of what they were calling a missed tackle, so I decided to start tallying those myself. I’ve been charting by position as opposed to player, so the missed tackles are categorized by edge defenders, interior defenders, nickel/down safeties, deep safeties, and outside corners. Any time a player gets an attempt at a tackle they get evaluated for it being a “good” tackle (an attempt resulting in getting the ball-carrier on the ground), or a “failed” tackle (an attempt with the ball-carrier getting past the defender or keeping their feet). When two defenders have arrived for a tackle at the same time, I’ve credited it to both of them, and if there is a big gang tackle or mass of people, I’ve credited to whomever got there first and if their initial tackle was sound.

I was trying to get a bigger sample size to compare the tackling game-to-game, but since this was an issue Saturday, it seems a good time now to break this out.

Through the first three games, I had charted the missed tackle rates as this:

Edge defenders: 31.3%

Interior linemen: 23.1%

Inside linebackers: 18.8%

Nickel/down safety: 9.1%

Deep safety: 18.2%

Outside corners: 30.8%

OVERALL MISSED TACKLE RATE: 22.5%

Here’s what I had the missed tackling as vs. the Wolverines:

Edge defenders: 50%

Interior defenders: 33.3%

Inside linebackers: 7.2%

Nickel/down safety: 20%

Deep safety: 33.3%

Outside corner: 41.7%

OVERALL MISSED TACKLE RATE: 28.9%

I don’t really have anything to compare that to, as I’m new to tracking this in 2025 and there isn’t anything I can compare it to for other teams. But, anecdotally, it’s seemed like this has been a generally poor tackling performance by the team, both by the eye-test and by those numbers above. Each of the position groups has sort of had a bad game: The interior’s missed tackle rate was almost 70% against Cincinnati and everyone else was largely fine, the corners were poor against Akron while the other positions were good, and then the edges whiffed a bunch against Houston Christian. There were also some major whiffs from everyone vs. Michigan, though the Wolverines are probably a step up in skill players from what Nebraska has seen.

Though I want to get a few more games of data before I draw any conclusions, I think a few things are developing. First is that the second- and third-level players in the spine of the defense haven’t really been the problem. The inside linebackers (Shavers, Marques Watson-Trent, Javin Wright) are rarely missing tackles: They’ve gotten 30 attempts at a tackle through four games, and I have just four of those as misses. Shavers had a great tackle on a screen in the second half vs. Michigan to end a drive. Likewise, the nickel position and box safeties (most often Malcolm Hartzog and DeShon Singleton) have gotten 16 tackle attempts and have just two clear misses. I thought Singleton was the worst tackler on the team last year, so that’s a big improvement. Buford had the bad whiff on the long touchdown Saturday, but the deep safeties filling from depth haven’t really been a huge liability in the season: They’ve made sound tackles on 13 of 17 chances. When the deep safety misses a tackle, it’s obviously going to look/feel worse because that usually means a huge gain, but from a rate-based perspective, they aren’t really the issue so far.

Much more damaging has been the front four and the corners: All three position groups are now missing over 30% (or close to it) of their tackle attempts. The front four missed six of their 15 chances at tackles against Michigan, and the outside corners missed 5 of their 12 chances. Donovan Jones, especially, had a few bad whiffs vs. the Wolverines, though he’s played extremely physically in the first four games; the willingness is there, he just failed to get people to the turf.

I’ll keep charting this and see how things develop, but with it such a talking point after Saturday, I wanted to share what I’ve charted it as so far.

Wide Zone Is Also An Issue

This is getting into diagnosing what plays specifically are working against the NU defense.

Wide Zone, or also sometimes called Outside Zone, was a play I mentioned Cincinnati had a lot of success with against Nebraska’s front in the opener.

Michigan also saw that and went to work on the Blackshirts with the concept. UM ran Wide Zone either as a pure run or tied to a run-pass option on 13 of its 54 non-garbage-time snaps. Those 13 plays gained 187 yards (14.4 yards per play), and included the 75- and 54-yard touchdowns, plus the 19-yard run on the third and 10 on the long Michigan drive in the fourth quarter. Michigan also ran three play-action passes off Wide Zone blocking action, one of which resulted in a 16-yard completion for another explosive. The double pass Michigan had open but whiffed the throw on was also off a faked Wide Zone RPO action.

This all is after Cincinnati ran Wide Zone 10 times for 7.5 yards a play in Week 1.

Wide Zone as a concept is a zone blocking scheme with the play-side linemen all shuffling/sliding laterally in an attempt to stretch the defensive front seven horizontally and either get defenders to overcommit or get backside seal-offs to generate rushing lanes. Despite its name, the ball is not really meant to go outside or wide — the play is designed to hit in the C gap, but it can really be taken anywhere and is ripe for cutbacks, with the back’s vision and ability to see the flow of the defense/seals being key. Wide Zone is the ultimate stress test of your front, meant to test for leaky gaps and send the ball there — which is why it became the dominant offensive system in the NFL in recent years.

Since switching to a 3-3-5, Nebraska has played a “one-gap” style, where its front-seven defenders are responsible for shooting upfield into certain gaps, as opposed to other philosophies where the front-seven players may be holding up offensive linemen and reading and reacting to what they do. A team that plays one-gap is always going to be vulnerable to Wide Zone; if your defenders are moving aggressively upfield, it’s going to be easier to catch one player in the front out of position, and a good Wide Zone team will be able to take advantage of that. Opposing offenses got NU with this concept under White plenty of times. But never to this degree.

Part of the worsening performance against Wide Zone are the stunt and tackling issues mentioned above. There have been several plays where a stunting player has run himself out of a gap and the ball has found the opening. But there have also been plenty of non-stunt or non-missed tackle reps where Cincy and Michigan had success with Wide Zone because of poor run fits, especially with the outside contain defender not sealing the edge, and because Nebraska’s interior couldn’t hold up to double teams. It’s something they have to work on during the bye week.

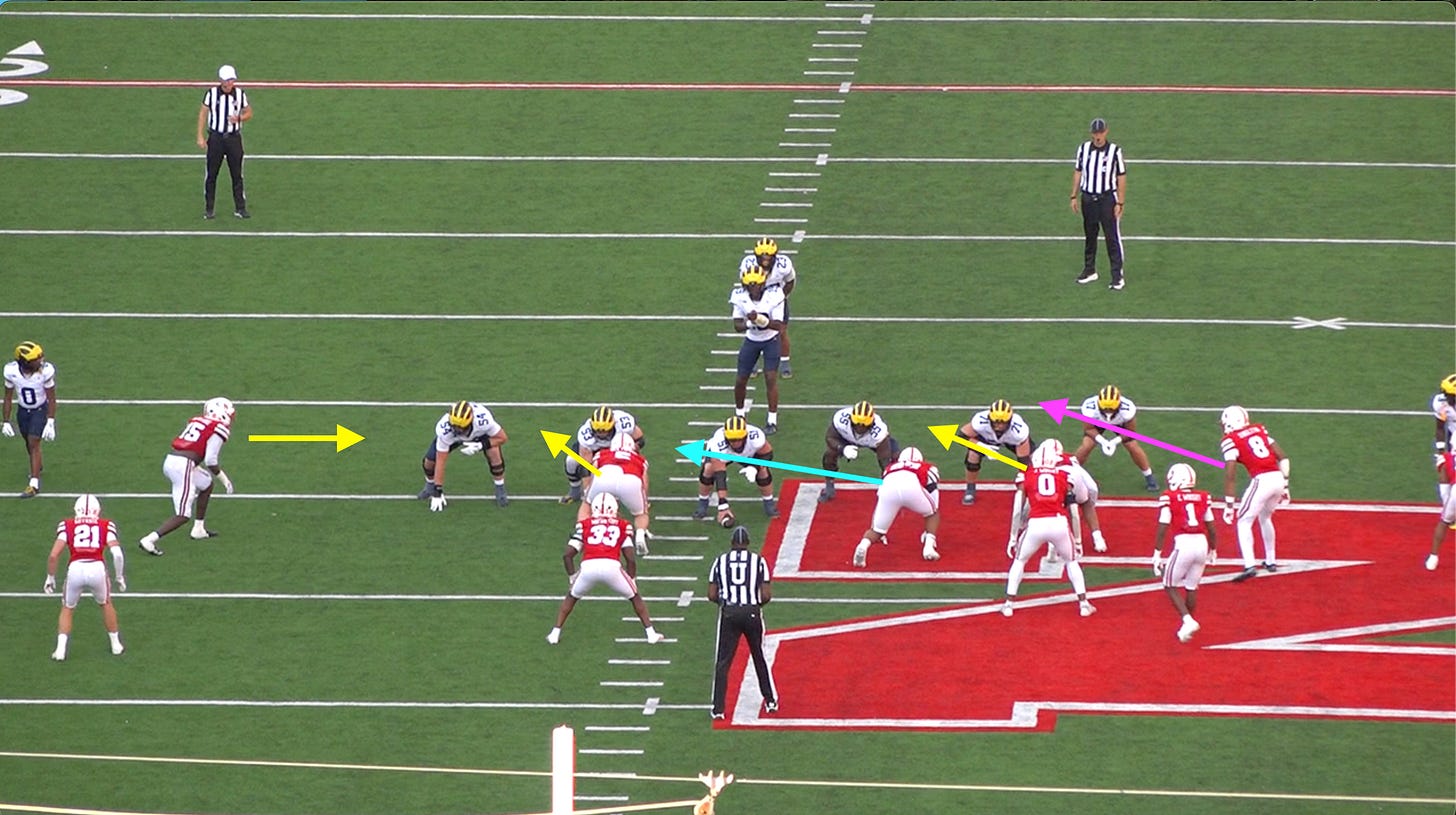

This is one of the few reps last Saturday where they defended it well:

This was out of a Bear front, with five defensive linemen across the line of scrimmage, something that NU went to on the last drive that had some success against the run. You can see Jones as the contain defender (#37) fills upfield and stays wide, forcing the back to not continue on an outside path. And on the interior, Nebraska’s two interior linemen have maintained the line of scrimmage and not been pushed backwards or displaced, which keeps any leaks from springing on the front and lets Riley Van Poppel fill once the back declares his path.

One Thing The Offense Probably Should Have Done More Of

Tempo.

Nebraska predominantly slowed the pace and huddled this game, only using no-huddle tempo on 12 of its 47 plays with an opportunity, about a quarter of the time. I imagine the thinking from the staff was to slow the pace of play against a more talented opponent to shrink the amount of possessions — and therefore opportunities — Michigan got.1 Nebraska was also switching personnel frequently, too, which requires huddling, and using a lot of motion, as previously stated, which makes play-calls more complex.

But huddling was also allowing Michigan to get in its complex pressure calls that were causing Nebraska so much trouble and confusion. It takes more time for a coaching staff to relay a specialty alignment with a stunt or sim pressure from the sideline into players than it does a base call, so against no-huddle tempos, defenses often call more base or vanilla plays. Which is why moving quickly is a popular answer against complex/tricky/blitz-happy defenses. But Nebraska was huddling on just under 75% of its opportunities, which was letting Michigan have enough time to communicate those complex calls from the sideline.

That bears itself out in the numbers. Overall, on Nebraska’s 60 plays that came after it huddled (either out of a stoppage where it was forced to huddle or in the general flow of the game where it chose to huddle), it had a successful play 26 times (43% success rate), and nine of the sacks and tackles for loss NU allowed came off those plays.

NU’s plays where it did move at tempo, though, had a 50% success rate, and most of their best drives all featured some use of tempo: The opening drive used no-huddle on three of its nine opportunities, the long drive in the third quarter that ended in the field goal used tempo on three of its seven chances, and the final touchdown drive also used tempo (out of necessity for the end-of-game situation). NU’s second, third, fourth, and fifth drives did not use a single snap of tempo, and huddled before third down, letting Michigan’s defensive staff relay in a blitz call Those four drives for NU efended in a sack, interception, sack, and sack, respectively.

There’s a little bit of noise here because a first down or good play will increase the likelihood of an offense using tempo before the next snap, so successful drives are already intrinsically going to have a higher tempo rate. But I also think it’s worth pointing out NU intentionally held back its tempo on drives it had success, and that largely was less effective than moving quicker. I think the staff could have maybe tried to be a little more aggressive in keeping Michigan’s defense off-balance.

Some Reasons For Hope On Defense

While I think it would be crazy to really praise the defense after that performance, the long runs are clouding some mildly optimistic things that happened.

NU came out of this game winning the efficiency battle on defense, and pretty convincingly, too, with a 61.1% success rate. The last two times Nebraska has played Michigan, the success rates were 35.6% and 34.4%, respectively. Those were probably better Wolverine offenses in 2023 and 2022, and UM certainly had some shoot-itself-in-the-foot moments Saturday, but Nebraska was winning the majority of the plays when Michigan’s offense was on the field and nearly doubled up its efficiency from the last time it faced the Harbaugh-Moore regime.

Second was that when Nebraska made Michigan actually have to pass and made Underwood have to play real quarterback, it largely dominated the reps. On passing downs (second downs of 8 yards or longer or third and fourth downs of five yards or longer) entering the final scoring drive, Nebraska was 10 for 12 on preventing a successful Michigan play. NU would go 2 for 7 on the final drive in those situations, but four of Michigan’s successful reps came off a designed swing pass, a handoff, and two designed quarterback runs. When NU was forcing pass situations, Michigan was not having any real success with a true dropback passing game.

None of that matters, though, if you just let yourself get blown apart with long runs. NU winning the efficiency battle and shutting down the Michigan passing game was a much less significant factor on that side of the ball than UM’s 18.5% explosive play rate, which is only topped in the last three years by last season’s Indiana game (22.7% explosive play rate allowed). And the quality of Michigan’s explosives makes Saturday probably a worse performance than IU: An “explosive play” in my charting is a 12-yard designed run or 16-yard designed pass, and most of Indiana’s were of that chunk-play-but-not-breakaway variety; Michigan ripped off three long scores on the first or second plays of drives for touchdowns. Efficiency and being good in passing situations doesn’t matter if you don’t actually force teams to drive on you because you’re giving up early-in-drive moonshots.

The secondary being good at tells me that this isn’t like 2022, where the front was a mess and nobody could stick with anyone on the back-end. If they can fix the front-seven busts, this is a competent — and possibly even good — defensive unit. But they have to fix the busts.

Turnover Margin Tracker

After Game 1: +2 (T-11th nationally)

After Game 2: +2 (T-25th nationally)

After Game 3: +4 (T-16th nationally)

After Game 4: +4 (T-19th nationally)

Nebraska has been undone in plenty of marquee games by turnovers, but you can’t really say that happened here. NU threw an early interception, but then the defense forced a fumble on Underwood as he tried to escape a pocket shortly after. Both teams played clean from there.

PFF had Raiola with two turnover-worthy throws (one of which was actually intercepted and one of which was dropped), though I think you could make the argument for several other throws into tight windows. The interception came off a little Slant-Out concept NU has run five previous times out of that same exact Empty formation with Dane Key and Luke Lindenmeyer stacked, where Key as the point runs a slant that really serves as a clearout/traffic creator/pick for Lindenmeyer on a 5-yard out to the sideline. Their previous reps of running this concept had gone 3-for-4 for 11.0 yards per play (and an additional nine-yard scramble); the long catch-and-run by Lindenmeyer in the second half of the Cincinnati game came off the same play out of the same alignment that they threw the pick on Saturday. Michigan had that alignment clearly scouted and knew what was coming, though, and had two guys squatting on it in zones, and Raiola threw it before really seeing if he had the access to throw to the outside.

Another factor here is that Michigan largely took the ball out of Underwood’s hands, giving him a lot of simplified-read and slide play-action concepts and a healthy dose of screens, which limited opportunities for Nebraska to get any splash plays beyond the fumble.

Which, it that was the strategy, it was undone by giving up three massive scoring runs on the initial plays of drives. Tough to ball control when they’re scoring three times 20 second into a drive.

Nice post as usual Jordan.

Was kind of expecting you to talk a little more about the offensive line:

Were our protection problems more of a scheme thing (besides going empty), a technique issue, or just talent? Is there anything that can realistically be done to fix it this season?

And why are we unable to consistently run the ball?

Do you put any of this on Donnie?

This was mostly defense focused which makes sense, but how are you feeling about the offense? It feels like Raiola has been better than last year (especially adjusting for OL issues) - do you agree?

Or is it just a case of Michigan forgetting to tackle/cover Jacory Barney twice and making me overly optimistic.