OFFENSIVE RECAP: 2023 Purdue

Pick routes!!!

Glossary of Terms1

Link to Charting Sheet2

DRIVE 1

4 Plays, 0.5 Yards Per Play

25% Success Rate

0 Explosive Plays, 1 Havoc Play Allowed

Purdue attacks Nebraska’s offense in an identical way to how Illinois did, with five-player-across Bear/Penny fronts on nearly every snap, heavy boxes, and man coverage with one safety aligned very deep. The Boilermakers would be in the five-player front on all but four of the game’s 57 offensive snaps, in a “heavy box”3 on all but two snaps, and in Cover 1 on all but six snaps. The similarity between the two teams is no surprise, with new Boilermakers coach Ryan Walters coming over from his stint as the Illinois defensive coordinator. But it’s an aggressive alignment designed to have plus-one defenders in the box at almost all times to stop the run, a tough matchup for a team like Nebraska that’s running the ball at one of the highest rates in the Power 5.

The Huskers try to take advantage of this heavy box and man coverage on the opening few plays, lining up in the I formation to ensure Purdue is keeping players in the spine of the defense, then tossing a swing screen out to the back and making the defenders have to sort through traffic to get to it.:

Nebraska has almost exclusively run or taken a deep play-action shots out of the I this season, so throwing it quick to the outside is already an opening-snap tendency breaker, and with the Huskers knowing Purdue would be in man coverage, they created leverage to the outside of the formation, knowing the man coverage defender would have to sort out all the traffic in the middle of the field to get out to cover the swing from the back. An additional wrinkle was that tight end Nate Boerkircher was lined up as the wide receiver to the playside to provide better blocking.

The blocking from the pulling linemen, Boerkircher, and fullback Janiran Bonner doesn’t hold up and the gain gets called back for a hold. But this would be a foreshadowing opening call from coordinator Marcus Satterfield, who utilized similar concepts frequently before the game was in-hand. It was also would have been Nebraska’s first successful screen play of the season, if it hadn’t been for the penalty.

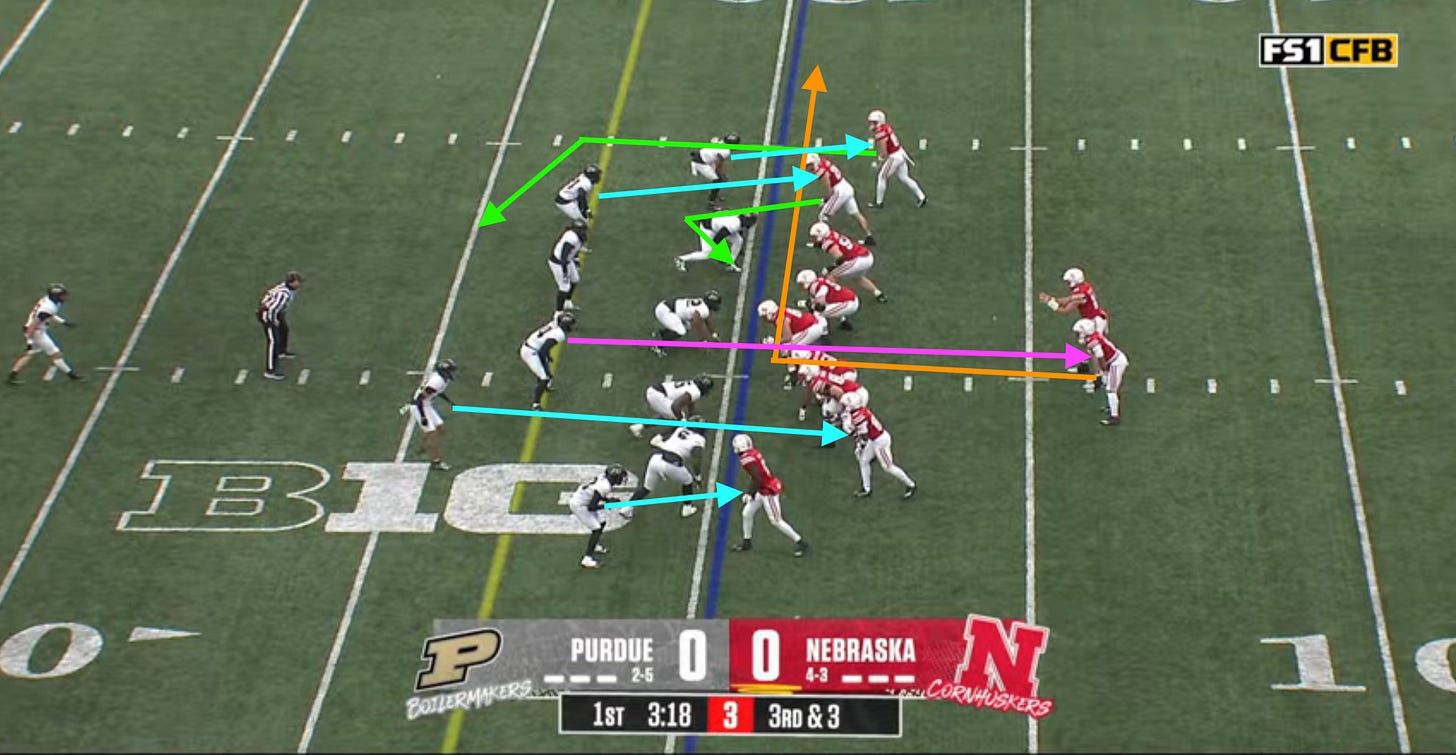

Satterfield continues to try to exploit the man coverage on the next two plays, a pair of downfield run-pass option plays:

The first is an Outside Zone read option to the backside of a trips formation, with an attached out route from the backside receiver. With Purdue’s shell the same and the secondary players manned up across the board, Satterfield knows that if he lines up in wide trips he’ll have just one defender to the backside of the formation, the corner over the lone receiver.

The line runs the Outside Zone action to the strength of the formation, and when the edge defender (circled in yellow below) crashes down with the line, quarterback Heinrich Haarberg pulls the ball and gets to the outside. From here, the play design has put the lone defender to the boundary in conflict: They can either cover the out route from the lone receiver with their man coverage responsibility (in blue), or they can come up to tackle Haarberg on the run. The corner stays with the receiver, so Haarberg pulls it down for an 8-yard gain.

This is, essentially, a modern take on the triple option, something Purdue would be vulnerable to with the amount of man coverage they run, with the secondary players’ eyes on defenders instead of what’s happening in the backfield. NU’s triple option rate entering was 3.4%, but would be nearly doubled on Saturday.

Satterfield goes to another man-beating RPO on the next snap, a Split Zone running play with a Slot Fade/Smash concept attached to the two-receiver side out of a doubles formation.

This isn’t a triple option-style RPO, with Haarberg having no run option, but rather a leverage one, with the quarterback having the ability to pull the ball and throw downfield if the receiver gets tight coverage and a safety isn’t aligned over top of them. Purdue starts in a rare two-high coverage look, which would indicate a give to the back on a running play, but one of the safeties flies down just before the snap to press slot receiver Jaiden Doss. The other Purdue safety also steps up into the box at the snap of the ball on the run action, and with Doss now getting one-on-one coverage and no safety capable of getting over the top of him, the read is now to throw the ball downfield on the RPO to the speedster on the fade route to the sideline. Haarberg delivers the ball right into Doss’ arms — one of his best throws since becoming a starter? — but it’s dropped.

It was still a nice play design to add optionality against Purdue’s aggressive tendencies. Nebraska hasn’t run many downfield RPOs this season, preferring to use short flat or quick routes on the few occasions it’s run RPOs at all, but would on six snaps this game. It had run just 16 total RPO snaps in the games leading up to this one.

But the penalty has led to a third and long, and the Huskers try a deep Yankee-concept passing play — a good single-high coverage beater — but the secondary gloves it up and Haarberg can’t scramble with Purdue also having a spy on, resulting in a coverage sack. A good drive of calls that results in a three-and-out because of a penalty and shaky execution.

DRIVE 2

3 Plays, 1.7 Yards Per Play

33.3% Success Rate

0 Explosive Plays, 1 Havoc Play Allowed

This possession is more standard play calling for Nebraska, but the execution doesn’t improve with two poorly blocked run plays setting up a third and long. Joshua Fleeks gets 5 yards out of the first when he breaks several tackles on an Inside Zone run that should have been a loss, then Anthony Grant takes a 3-yard loss on a Counter play that has immediate penetration.

On the long third, Nebraska tries the Post-Wheel play it had a lot of success with against Illinois, but the Boilermakers drop out of a pressure look and confuse Haarberg, resulting in a short scramble and forcing another punt.

DRIVE 3

15 Plays, 5.9 Yards Per Play

53% Success Rate

3 Explosive Plays, 1 Havoc Play Allowed

Purdue had played Cover 1 every snap but one to this point in the game — and would for all but two snaps of this drive — and Satterfield puts on a strong showcase of exploiting the man coverage with pick and flat routes aimed at making Purdue’s second-level defenders chase NU’s skill guys through traffic to the edges.

The first example comes on the initial third down, out of a quick play-action pick play to the flat:

The whole goal of this play is to get Nebraska’s back into the outside flat with space to run against man coverage. NU starts in a two-back look, with its receivers condensed near the formation to keep all of Purdue’s defenders in the spine of the field. From there, the slot receiver, Doss, motions out of the backfield to a tight split, taking a route where he fakes to the field side of the formation before spinning back and going to the boundary. This play will only work against man coverage, so by having Doss take the exaggerated route, NU is making especially sure it will be getting man coverage. You can see one Purdue defender step-for-step mirror Doss; if it were zone coverage — with defenders responsible for areas and not individual offensive players — no one would have followed him. The Huskers have on the right look to beat Purdue’s defense:

From there, the ball is snapped, and Haarberg gives a token run fake to Fleeks before dropping into a three-step pass set, indicating to Purdue it will be a standard drop-back passing play. The linebacker responsible for Fleeks in man coverage (purple arrow) is frozen from moving laterally by the fake, and Fleeks comes straight down the field toward him. To the playside of the formation, both the condensed receiver, Alex Bullock, and tight end, Thomas Fidone, are working what look like short routes from the outside of the formation to the inside.

But the picture changes when Fleeks quickly breaks outside to the boundary, running just shallow of Bullock’s and Fideone’s routes and looping back behind the line of scrimmage. The linebacker is still flat-footed from the run fake and is now steps behind chasing Fleeks to the outside, and he has to navigate the traffic of Bullock, Fidone, and the two defenders covering them. All the bodies in the area create a natural pick on the defender, like in basketball, springing Fleeks for an easy catch-and-run. Fidone almost puts too fine a point on it when he more-or-less throws himself at the chasing Purdue linebacker on a block, but the ball is luckily thrown behind the line of scrimmage, otherwise he probably would have had the gain wiped out with an offensive pass interference.

After a couple short runs and a nice conversion off of Mesh — another man-coverage beater — Satterfield again attacks the man coverage to the edges for another explosive play:

This is a play NU has run a few times this season with a bit of success, an Inverted Veer concept that uses Jet motion from the slot receiver as the handoff player. While this is a read play that Haarberg has the option of keeping behind the pulling guard, adding the Jet motion as a wrinkle is intended to compromise Purdue’s man coverage in the same way as the pick play above, with the man coverage defender trailing Fleeks — No. 10 for Purdue — having to navigate and fight through all of the bodies in the box as Fleeks runs unimpeded to the edge, giving Nebraska one fewer player to block to the playside.

After a few more short runs — including on a QB Counter-Bubble RPO that also is applicable to Satterfield attacking the edges — set up another third down, it’s time for another pick play, this time less of a screen and more off a standard Spot concept:

Nebraska again starts in a condensed look, with no receiver to the field outside of the hashes. Satterfield again uses cross-field motion to identify man coverage and make a Purdue defender navigate traffic, this time from the X receiver Ty Hahn. The outside corner covering him does orbit around the secondary and get even with Hahn just before the snap as Hahn settles into the condensed No. 3 spot. But after the snap, Satterfield has the same corner (purple arrow) run through traffic again, with the two receivers outside of Hahn running back toward the formation or on a vertical stem as Hahn breaks toward the field sideline as the flat route on a Spot concept, creating another pick:

The defender can’t sort through the traffic to catch up until Hahn is already 5 yards past the first down. Satterfield also has a designed roll-out from the quarterback on here, giving Haarberg another easy-access throw for his sidearm deliver to convert.

Nebraska then runs two RPOs also designed to beat man to the edge, the first an Inside Zone/Swing Screen concept on the next snap that is dropped, with pre-snap reverse Orbit motion across the formation to again take advantage of the man coverage. Purdue sniffs this one out and Fidone misses a block, with the dropped pass preventing what would have been a sizeable loss. Two plays later, it tries to run its Split Zone-Arrow RPO across the formation to the tight end, but Haarberg misreads it, the play is blown, and he ends up keeping it himself up the middle for a first down near the goalline.

After a failed QB keeper, Nebraska converts the touchdown using one more of these plays:

NU starts out with the receivers spread wider this play, but just before the snap, Fidone motions in to the formation and a condensed split, bringing the man coverage defender covering him with him to the interior of the formation and inside the alignment of X receiver Bullock. Bullock then runs an inside-breaking snag route after the snap right into Fidone’s defender, preventing the defender from following Fidone as he breaks back outside to the flat for an easy touchdown. Chef’s kiss:

Nebraska ran seven plays this drive featuring some form of man-beating concepts to the outside, using them to convert three first downs, get two explosive plays, and score a touchdown. Overall, Satterfield ran motion on this drive on 11 of the 15 plays. He had clearly found a way of manipulating the Purdue defenders’ leverage and alignments before and after the snap.

DRIVE 4

1 Play, 73.0 Yards Per Play

100% Success Rate

1 Explosive Play, 0 Havoc Plays Allowed

After a drive in which Satterfield exploited the tendencies and predictability of the defense he was facing, Walters and Purdue came back out in … the exact same defense, with heavy fronts and tight man coverage. The Boilermakers summarily give up a 73-yard touchdown on a fake option pass on the first snap.

I broke down this play last week, so I won’t get too much into it here. The differences between this play and last week’s are the formation — out of wide trips instead of the I formation — and the routes — this is more of a Yankee/Deep Crossers concept, while last week’s was more of a Sail/Flood — but the goal and result here are the same: getting the deep safety to bite on the backfield action so a receiver can run past them to get a one-on-one with a corner expecting downfield help.

You can see the Purdue safety (No. 31, the deepest player on the field near the top hash) step forward with the option fake to fill on the run. The play is essentially over at this point assuming a good throw — with no deep safety over the top to take crossers, this is now a Purdue nickel defender playing outside leverage trying to run one-on-one toward the inside of the field with a track-star receiver. Haarberg, for his part, puts a really nice ball on it and gets to show off his arm strength a bit. After a couple pretty horrible performances as a dropback passer in the last several games, I thought this was by-far Haarberg’s best game from both a passing processing and ball-placement perspective.

DRIVE 5

5 Plays, 2.4 Yards Per Play

20% Success Rate

1 Explosive Play, 0 Havoc Plays Allowed

DRIVE 6

2 Plays, 4.5 Yards Per Play

50% Success Rate

0 Explosive Plays, 0 Havoc Plays Allowed

DRIVE 7

1 Play, 1.0 Yards Per Play

0% Success Rate

0 Explosive Plays, 1 Havoc Play Allowed

DRIVE 8

3 Plays, 4.0 Yards Per Play

0% Success Rate

0 Explosive Plays, 0 Havoc Plays Allowed

But after the successful drive targeting Purdue’s generic structure and man coverage tendencies and the big pass play stake NU to a 14-0 lead — and a blocked kick return touchdown that happens between this stretch to make the score 21-0 — Satterfield and Nebraska’s offense go into basic, run the clock mode. On the fifth drive, Satterfield tries an end around off NU’s under-center bunch formation Counter play that almost goes big, and Drive 8 opens with another attempt at the man coverage-beating swing screen play tried on the game’s first snap, but otherwise the play-calling goes back to the basics and never really gets back to the designer man-coverage beating stuff we saw NU have success with on Drive 3. And it’s not because anything changes with Purdue’s defense, still in its five-man front, with +1 in the box and Cover 1 behind it.

We see a lot of spread trips formation Inside Zone read plays (4 of 11 snaps this sequence) and Freeze Option (3 plays this sequence). One of these drives is a before-halftime clock-killer and another is a first-play fumble, so there’s a chance Satterfield would have been more aggressive he had had more time and opportunity to cook. But after the long passing play score, Nebraska would have just eight successful plays in its final 35 offensive snaps (a 22.9% success rate) and the play-calling clamming up was a huge factor in the dropoff in offensive success.

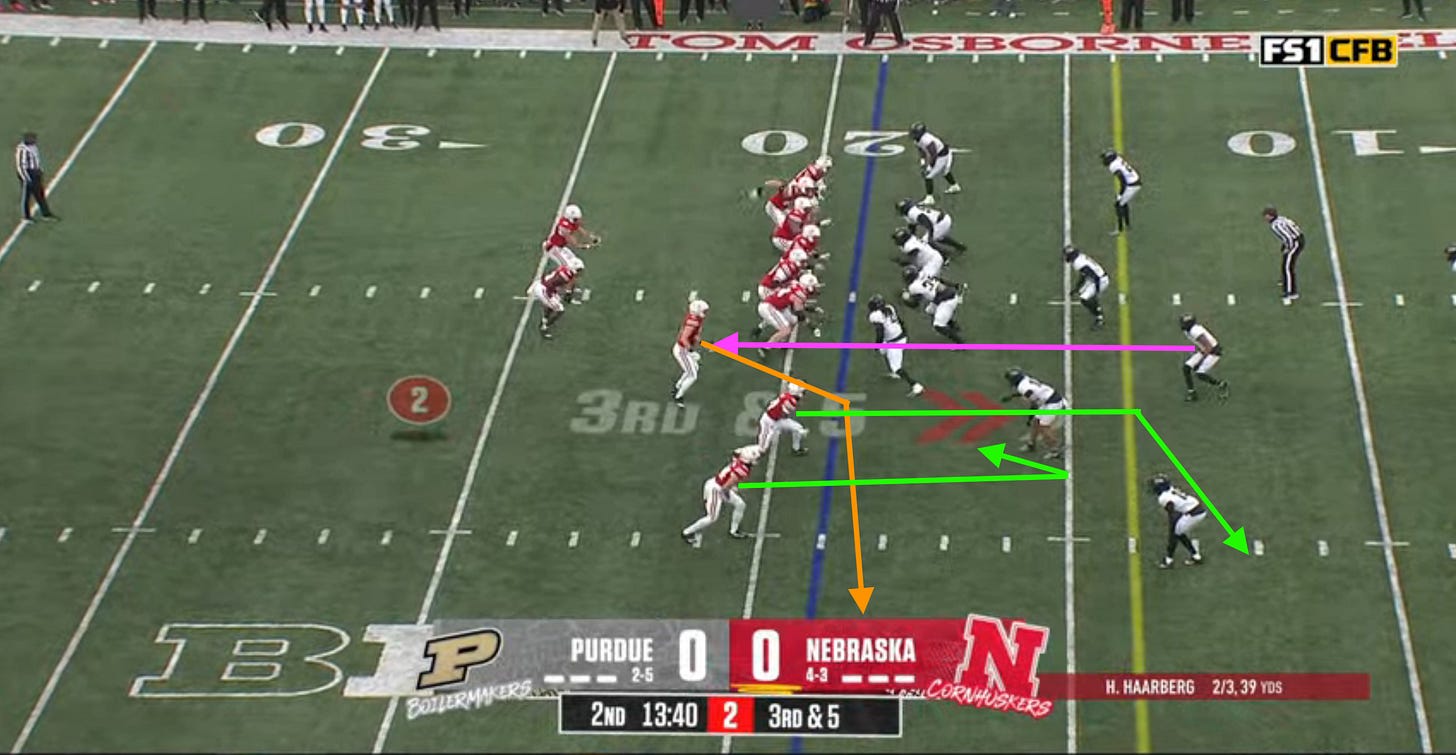

Nebraska did debut one new play in this sequence, a read play that conflicts the 3 technique instead of the edge player, with the guard over top pulling to create numbers for the give read:

Nebraska would run this play one other time on the final drive, with a quick screen attached. If you remember from the Illinois game, Nebraska tried to attack that similar defense with plays targeted at the 3 technique a lot.

DRIVE 9

6 Plays, 1.2 Yards Per Play

33.3% Success Rate

0 Explosive Plays, 1 Havoc Play Allowed

The run-out-the-game offensive strategy continues here, just out of the I formation. Nebraska uses Pro I looks on the first five snaps, a wide receiver lead Counter after motioning in Bullock and then four plays out of its Load Option package. One of those was a play-action fake option shot off deep crossing routes that does draw a pass interference penalty that looked like it could have generated a big play had the receiver not been pulled down.

With Purdue playing so much man and heavy fronts, the outside option plays were always going to be a big part of the gameplan. Option plays are more effective against man coverage because the second-level defenders all have their eyes on specific receivers, not what’s happening in the backfield. NU entered the game running these outside option plays on about 10.9% of its run calls but would use them for 25.6% of its run calls on Saturday.

DRIVE 10

5 Plays, 2.8 Yards Per Play

40% Success Rate

0 Explosive Plays, 0 Havoc Plays Allowed

DRIVE 11

2 Plays, -5.5 Yards Per Play

0% Success Rate

0 Explosive Plays, 2 Havoc Plays Allowed

After the I formation package didn’t really work, Satterfield goes back to the read option out of shotgun for these two drives, though the results don’t really get much better.

He opens Drive 11 with two outside Freeze Options and an Inside Zone read, picking up an initial first down. Nebraska has called a running play on 16 of the last 20 plays at this point, so Purdue brings a corner blitz on the third play of this series to stop the run — one of just two snaps all game where the Boilermakers brought an additional rusher than their five-man front — though NU’s play-call goes the opposite direction from it.

Potentially looking to take advantage of Purdue now bringing more heat against the run, Satterfield calls a play-action boot with a heavy guard-tight end Counter blocking fake out of a bunch formation, with just two players out in routes, but Purdue isn’t fooled and the pass is incomplete. On third and 8, Nebraska again moves Haarberg on a rollout Flood concept, which is also incomplete to the sideline.

I’ve been surprised by the lack of quarterback movement Nebraska has used this season, with QB rolls happening on just 6.3% of Nebraska’s passing plays. By rolling out, you make reads easier on your quarterback, with the passers only having to evaluate half the field and one to two defenders instead of reading the whole defense and coverage over the width of the field. With Haarberg’s lack of experience and struggles in the dropback game, I think it would be beneficial to get him on the move more and give him simplified decisions. Nebraska’s rate of rollouts was 20% on Saturday, though some of that could be a situational answer against Purdue’s agressive defense. But it also could be Nebraska’s offensive staff embracing more QB movement.

The next drive is a disaster, with Satterfield again trying to burn Purdue with an unexpected pass for the third straight snap — a third fake option deep shot of the game that ends with Haarberg taking a wallop for a 7-yard loss — and then another rip-out fumble as Haarberg is held up. How these guys weren’t going with two hands on the ball after they watched Purdue rip at every ball they could is beyond me.

DRIVE 12

4 Plays, 2.25 Yards Per Play

0% Success Rate

0 Explosive Plays, 1 Havoc Play Allowed

DRIVE 13

6 Plays, 8.0 Yards Per Play

33.3% Success Rate

1 Explosive Play, 0 Havoc Plays Allowed

Nebraska closes out the game with pulling lineman, calling plays with pullers or cross-blocking motion on eight of the final 11 snaps, including four plays of Counter. The four Counter snaps over this drive go for a combined 42 yards and a 50% success rate, including a long touchdown by Johnson to essentially end the game. This was also a big Counter game against the five-player front, with a 20.9% Counter usage, nine percentage points higher than the season average of 11.9% entering.

Coach Matt Rhule made the decision to insert backup quarterback Jeff Sims for this first drive after Haarberg’s fumble on the previous play. NU’s fumbling has been a massive problem — it leads the FBS in virtually every fumble metric — and I don’t think Haarberg has been any more careful with the ball than Sims, just punished less as defenses have recovered a lower rate of his fumbles. So I get the desire from Rhule to make a point fumbles aren’t acceptable. But I also don’t think fumbles are totally a question of a player’s lack of focus or discipline and are far more due to variance or luck than the general football fan gives credence to. And taking your best players off the field for a mistake is never going to be something I understand or support.

Furthermore, taking Haarberg off the field for Sims — who routinely struggled with basic football pre-snap operation and things like timing the motion to the snap count — was a pretty clear no from me. In just the four snaps we see Sims this game, he almost snaps the ball into a motion man — Bonner is leading on a counter play and has to stop his motion to avoid being hit with a snap — turn the wrong way on a quarterback Arc-lead play designed for him to run the ball to that direction, and fumble on a pretty standard hit. I would have been a lot more supportive of Rhule’s point-proving with Haarberg had he replaced Haarberg with an actual functional quarterback, but Sims can’t competently run an offense right now, so the effect is a little dulled. So I found that whole sequence a little silly.

Yards Per Play measures how many non-penalty yards NU gained on a possession divided by its non-penalty snaps, a measure of its efficiency. Success Rate measures how often an NU play gained 50% or more of the yards it needed on a first down, 70% or more of the yards it needed on second down, or 100% or more of the yards it needed on third or fourth down. An Explosive Play is any designed run that gains more than 12 yards and any designed pass that gains more than 16 yards. A Havoc Play Allowed is any tackle for loss, sack, fumble, interception, pass break-up or batted ball NU allows.

I count a “heavy” box as any where the defense has one or more defenders in the box than Nebraska can block. So in a spread formation with only five linemen to block, six defenders is a heavy box. In a two-tight-end-attached alignment, eight defensive players would be a heavy box.